I was reminded the other day of two things about prescriptive usage rules: (a) the power that comes with feeling like you know rules of usage that other people don’t (or have forgotten); and (b) the sometimes fine line between a usage rule that promotes standard usage and one that falls into nostalgia, stuffiness, or obscurity.

As I’ve written about on Lingua Franca before, I am a fairly meticulous copy editor (or at least I like to think I am). I try to ensure that my own and others’ formal academic prose adheres to most standard usage conventions. As part of this enterprise, for the past 15 years, I have been correcting “hone in on,” as in “if we hone in on this question,” to “home in on.” I will admit that I have sometimes felt a little self-satisfied making the change in other academics’ work, knowing that at least some of them will be surprised to learn that this is the original form of the verb.

Historically speaking, my correction has legs. The expression originally was home in on, employing the verb home that is used to describe planes homing in on targets and, before that, homing pigeons doing their homing work. It first appears in reference to planes, missiles, and vessels in 1920, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, and the citations show the forms home on and home toward in addition to home in on. The verb had expanded to encompass the figurative meaning of “to focus on, make the sole object of one’s attention” by 1955.

By 1965, according to the OED, the expression had come to be understood by some speakers and writers as hone in. The citations show that hone in can be used to describe moving directly toward something (e.g., “A wasp had begun to circle round the bowl … , gradually honing in on the ripe glistening fruit,” from Eva Figes’s 1983 novel Light) and to describe focusing intense attention on something (e.g., “A few who know the wearer well recognize that something is different without honing in on the hairpiece,” from a 1967 New York Times article). It is easy to see how speakers got there, given the word hone’s connotations of sharpness or exactness. Just like we might hone a knife, we are honing a question or a focus (or a movement in a specific direction) down to what we’re really interested in.

Then the other day, I encountered this sentence in a graduate student’s essay: “Or, a tutor might home in on an argument which runs counter to the tutor’s own beliefs.” The verb “home in” immediately jumped out at me: it read as stilted, perhaps a little overly careful, perhaps even pedantic. And I knew that it was there only because I had corrected “hone” to “home” in an earlier draft!

I was left wondering whether home in on is losing its status as the standard form, or at least as an unmarked form in the standard. If so, I really should stop changing the now perfectly standard hone in on.

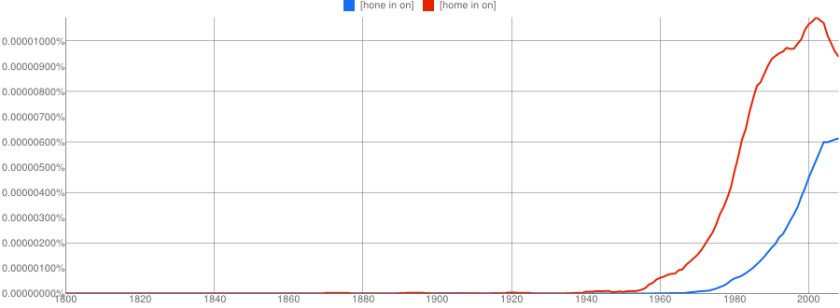

A search of Google Books in English from 1800 to 2008 with the Ngram Viewer shows that home in on is still more frequent than hone in on, but the gap is narrowing, with a notable drop in the use of home in on after 2000. (I have not had time to sort through to see how many of these instances refer to the action of planes/missiles/etc. as opposed to the figurative action of focusing one’s attention.)

ADVERTISEMENT

In my forthcoming book Fixing English: Prescriptivism and Language Change, I describe four kinds of prescriptive language rules: (a) standardizing; (b) stylistic; (c) restorative; and (d) politically responsive. Restorative rules are those that promote older usages as correct primarily because they are older (and sometimes seen as more “pure”), not because they are currently standard. My favorite example of the third category is the “rule” that the word nauseous really does and should mean ‘nauseating’. That is no longer, of course, the standard use of nauseous: It is much more standard to say “The roller coaster made me nauseous,” not “The roller coaster is nauseous.” The latter sentence is arguably moving toward obsolescence.

These four categories of prescriptivism are permeable, and usage rules may move among them. I think the “rule” that hone in on should be home in on is well on its way into the restorative category, if it doesn’t already have one foot in there. My correction then is not, in fact, necessarily enforcing standard usage: It is, I think, starting to become persnickety and has the potential to make the prose sound stilted.

I have vowed no longer to home in or hone in on which of the two verbs other writers use to talk about focusing intense attention on something. I’ll be interested now to see which verb I settle on for my own formal prose in the years to come—or whether I just overuse the verb focus on and avoid the question entirely.

This blog was originally posted on The Chronicle